The Greek War of Independence from 1821 to 1829 on Crete.

The revolution in Crete

The Greek War of Independence kicked off in March 1821, stirring hope and rebellion against the Ottomans. Crete joined in about two months later, but the islanders faced a ton of challenges—scarce weapons, rough communication with the mainland, and all the usual headaches of being far from the action.

Still, the spirit of freedom was simmering. Cretans had put up with Ottoman rule for over four centuries, so you can imagine the pent-up frustration.

The first sparks of revolt flared up mostly in places like Sfakia, Glyka Nera, Loutro, and Panagia Thymiaki. These areas weren’t strangers to resistance—especially Sfakia, where folks had already fought back hard during the failed 1770 revolt led by Daskalogiannis (that one ended pretty badly, with brutal reprisals in Heraklion).

Throughout April and May 1821, local leaders held several meetings to get the ball rolling. Notable dates? 7 April at Glyka Nera, 15 April and 21 May at Loutro, and 29 May at Panagia Thymiaki. That last date was chosen on purpose—it echoed the fall of Constantinople on 29 May 1453, adding a bit of symbolic weight to the cause.

The large island is located quite far from the rest of Greece, and therefore sending military help was difficult.

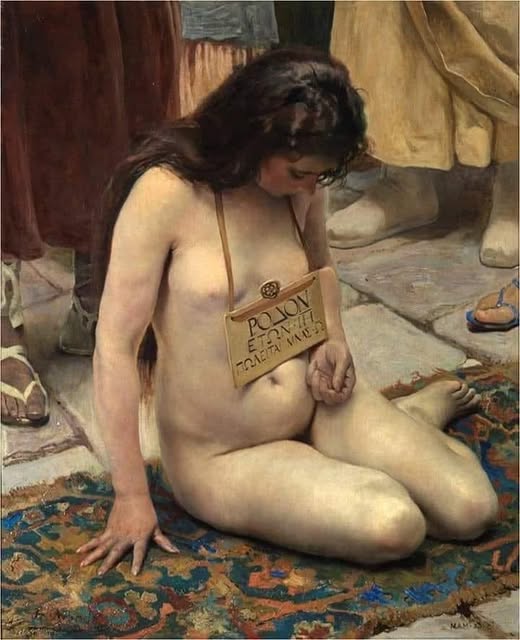

In addition, Crete was home to a sizable Muslim minority, which accounted for almost a third of the population. Despite these adverse circumstances, joining the revolution was raised at meetings with local leaders and dignitaries in Sfakia, and the decision to revolt was made there.

The Turks responded by hanging the bishop of Kissamos, imprisoning others, and continuing the persecution of clergy and laity in the region.

Monks, regular folks, everyone chipped in. The Turkish response was harsh, but it couldn’t really snuff out the Cretan drive. The first big clash came on 14 June 1821 in Loulos, Chania. There, a Janissary unit was defeated and its leader killed. This event set the tone for what was to come. That one set the tone for what was coming.

The Turks responded by looting and slaughtering civilians. However, fighting continued with victories by the Greeks in July 1821, but in August a powerful Ottoman force arrived at Sfakia. The Ottomans defeated the Sfakians and continued to commit atrocities and murder people.

But the rebellion did not stop. Dimitrios Ypsilantis, at the request of the Cretans, appointed Michael Komninos Afentoulief as the general commander of the revolution in Crete. Despite the failure of an attempt to capture Rethymno, the Greeks achieved victories in the region of Mylopotamos as well as in front of the fortress of Chania.

Petros Skylitsis Omiridis later arrived in Crete as a representative of the Greek central administration. A local assembly was held, the result of which was the institutionalization of the ‘Transitional Policy of the Island of Crete’ on May 21, 1822. Afentoulief, with his title of ‘Prefect General of the Island’, assumed the general leadership of the Greek revolution in Crete.

By May 1822, a good chunk of Crete was out of Ottoman hands. But the Ottomans weren’t giving up—they called Egypt for backup. Muhammad Ali, the Egyptian ruler, sent his son-in-law, Hassan Pasha, along with a formidable fleet and troops.

On 28 May 1822, Souda Bay saw the arrival of 114 ships—30 Egyptian warships and 84 French transports. That was a game-changer. The Egyptian intervention made it clear that Crete was a prize everyone wanted to keep in the Ottoman orbit.

Key Elements of the 1821 Cretan Revolt

Element |

Details |

|---|---|

Start Date |

April 1821 (series of meetings); first battle June 14, 1821 |

Main regions |

Sfakia, Glyka Nera, Loutro, Panagia Thymiaki |

Opposing forces |

Local Cretans, Greek revolutionaries vs. Ottoman Empire and Egyptian allied forces |

Important figures |

Sfakian leaders, monks, members of Filiki Eteria (Friendly Society), Hassan Pasha (Egyptian) |

Significance |

Early major conflict in the Greek War of Independence on Crete, strong local resistance |

External forces |

Arrival of Egyptian fleet in 1822 to support Ottomans |

Cities involved |

Heraklion, Chania, Rethymno, Souda |

The revolt on Crete wasn’t just about battles. There was a lot of behind-the-scenes diplomacy and some support from the Greek government and other allies. With its key ports like Souda, the island was a strategic hot potato for both sides.

The Role of Cretan Society

Cretan society was at the heart of the revolt. People were driven not only by dreams of independence but also by old wounds—memories of oppression and failed uprisings. Monks and rural folk often took the lead locally, teaming up with the Filiki Eteria, that secret group organizing the revolution.

The mountains—especially around Sfakia—were a big help. The Ottomans had a tough time controlling those rugged spots, and the Cretans knew how to use the terrain for guerrilla tactics.

Challenges during the Uprising

But let’s not sugarcoat it: the Cretans had a rough go. Weapons were scarce, and support from the mainland wasn’t exactly steady. Communication was a mess, making coordination across the island tricky at best.

When the Egyptians showed up in 1822, things got even tougher for the rebels. The Ottomans and Egyptians used blockades and sieges, especially in cities like Heraklion and Rethymno. The fighting was brutal, and both sides paid a heavy price.

Summary Table: Timeline of Key Events

Date |

Event |

|---|---|

March 1821 |

Greek War of Independence begins |

April-May 1821 |

Cretan leaders meet to plan revolt |

14 June 1821 |

First battle in Loulos, Chania |

May 1822 |

Most of Crete is free from Ottomans |

28 May 1822 |

Egyptian fleet arrives at Souda |

The Egyptian intervention

In May 1822, an Egyptian fleet of many ships sailed for Souda. Several thousand infantrymen, consisting mainly of Albanian mercenaries, and several hundred horsemen, led by Hassan Pasha, landed on the island.

In their first clash with the Greeks, the Turkish-Egyptian army was defeated at Malaxa, but immediately afterwards the Greeks succumbed to the counterattack of the Ottomans, who were superior in armament and organization.

Similar to the internal disputes in the Peloponnese, disputes arose between the local leaders and Afentoulief, leading to Cretan exhaustion and waste from trivial internal conflicts. The Hydraean Emmanuel Tombazis replaced Afentoulief. Tombazis’ presence revived the revolution, especially in western Crete. The fortress of Kastelli (Kissamos) was taken.

This was followed by the siege of the fortress of Kandanos in Chania. However, this victory was overshadowed by the breach of the agreement made with the Turks, when Cretans attacked and killed many of the departing Muslims. This reprehensible act caused the Turks to no longer trust the assurances of the Cretans, and so they were no longer willing to surrender voluntarily.

In June 1823, another Egyptian fleet arrived and a large Egyptian army with French officers under Hussein Bey landed in Crete. The result was the suppression of the revolution in Crete.

Tombazis failed to unite the local leaders for joint action against the enemy, while it was not possible to bring in reinforcements from Greece. In the meantime, the Egyptians continued to suppress the revolution with great force as Hussein Bey marched against Messara and entered Rethymno.

In March 1824, Hussein moved to Sfakia, which was the heart of the revolution. The fall of Sfakia caused the morale of the inhabitants of many regions to collapse until they finally surrendered.

On April 12, 1824, the ‘Governor of Crete’, Emmanuel Tombazis, left the island. This was the end of the revolution in Crete. However, guerrilla fighting against the Egyptian-Turkish troops continued in the mountains with sporadic raids.

Cretan patriots who had fled to the Peloponnese subsequently asked the provisional Greek government for help in capturing the fortress of Imeri Gramvousa, a small rocky island at the western end of Crete protected only by a few guards.

In August 1825, three ships were dispatched and a few hundred men went ashore at Castelli (Kissamos) and occupied the area. The few Turkish guards of Gramvousa surrendered the fortress without a fight after a deception maneuver.

The Greek government could provide only limited reinforcements, while the governor of Crete, Mustafa, was a stubborn opponent. After the fall of Messolonghi on the mainland, defeats and further disappointments followed. Despite all efforts, both by the Cretans themselves and by the Greek government, it was not possible to achieve a decisive victory in Crete.

In January 1828 there was another landing on the island by the epirote Hatzimichalis Dalianis with 700 men. The following March they took possession of Frangokastello, a castle on the south coast in the region of Sfakia. Soon the Ottoman governor of Crete, Mustafa Naili Pasha, attacked Frangokastello with an army of 8,000 men. The castle fell after a seven-day siege and Dalianis perished along with 385 men.

The great European powers opposed the annexation of Crete and Samos by Greece because of the resistance of the Sultan in Constantinople. In the case of Crete, complications were added by the Egyptian Mehmed Ali’s claims to it, which were also supported by France and Britain at the time.

In 1862, King Otto of Greece was forced to abdicate, but despite tight coffers, he used his entire annual income to finance a shipment of weapons from his Bavarian exile in 1866 to the Cretans, who were again in revolt against Ottoman rule. This uprising also failed and its landmark today is the then besieged Arkadi Monastery near Rethymno and November 8 is a national holiday in Crete.

Thus, Crete had to wait until 1898 for its independence and the annexation to Greece took place only after the First Balkan War in 1913.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who were the key Cretan leaders during the Greek Revolution of 1821?

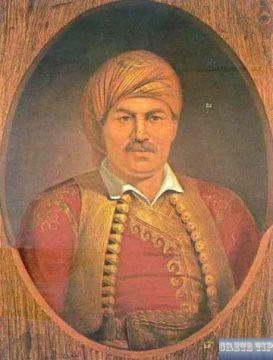

Several notable figures led the Cretan resistance. Daskalogiannis, the rebel from 1770, is often mentioned as an inspiration for later uprisings. Other local chieftains stepped up too, organizing the fight against the Ottomans and keeping the island’s fight alive.

What part did Crete play in the Greek Revolution of 1821?

Crete was a real hotspot for resistance. People picked up arms early—battles were happening by April 1821. Even with harsh reprisals, Cretans didn’t back down for years.

Which areas in Greece started the revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1821?

The uprising kicked off in several places: the Peloponnese, Central Greece, and islands like Crete. These regions tried to coordinate attacks and light a fire under the national revolution.

Can you name some less famous individuals who supported the 1821 revolution?

Not everyone who mattered made it into the history books. Lots of local fighters, priests, and regular townsfolk played vital roles. Their efforts kept the rebellion going, even if we don’t know all their names.

What important events happened in Crete during the 1821 revolution?

Some of the key moments? The first battles in villages like Loulos in June 1821. There were also sieges, scattered skirmishes, and plenty of small acts of resistance that defined Crete’s long struggle during the war.

Who was a revolutionary martyr in the 1821 fight who died in 1838?

One of the more memorable martyrs was a revolutionary who kept fighting long after most thought it was over.

He died in 1838, either executed or in captivity—it’s a bit hazy, but his sacrifice stands out, especially since it happened well after the war had officially ended.

References and literature

dtv-Atlas Weltgeschichte (Band 2 – Von der Französischen Revolution bis zur Gegenwart)

THE GREEK REVOLUTION OF 1821: The Transition from Slavery to Freedom (Vassilios Moutsoglou)

The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary (Paschalis M. Kitromilides)

Die Unabhängigkeit Griechenlands (Ruben Ygua)