For decades, the faces of those executed during Greece’s darkest hour remained hidden from history. Now, archival research by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) has given one of the victims – a young man from Chania – a name and a story.

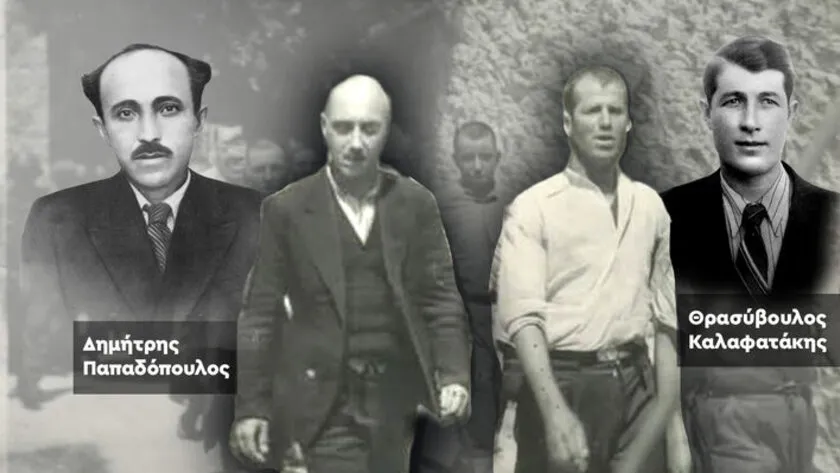

On 1 May 1944, around 200 communist prisoners were executed at the Kaisariani firing range in Athens – a massacre that is considered one of the most tragic chapters in the history of the Greek resistance movement. Recently, the KKE made a significant historical breakthrough by identifying two of the victims from preserved photographs and meticulous archival research: Thrasybulos Kalafatakis, a 30-year-old from Chania, and Dimitris Papadopoulos, of Pontic descent.

The discovery of the Kaisariani photos

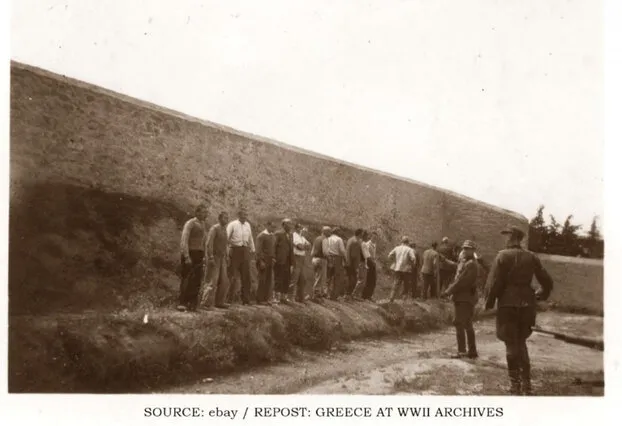

A sensational discovery that has caused a stir in Greek historical and scientific circles: previously unknown photos documenting the mass execution in Kaisariani on 1 May 1944 have unexpectedly appeared on the online auction platform eBay. For the first time in over eight decades, the world can see the faces of the victims and perpetrators, frozen in a single, harrowing moment.

The appearance of these photos on Saturday, 14 February 2026, has sparked an intense debate about the preservation of history, the ethics of documenting Nazi war crimes, and the obligation of nations to restore and honour the memory of those who died at the hands of state violence. What began as an ordinary online auction has become an extraordinary window into one of Greece’s darkest hours.

The discovery: How unknown photos appeared on eBay

On Saturday, 14 February 2026, an attentive community of historians and researchers noticed something extraordinary on eBay: a collection of original photographs documenting the Kaisariani execution site on 1 May 1944. The photos had apparently been in private ownership for more than 80 years – probably belonging to a German family with a relative who was stationed with the occupying forces in Greece during the Second World War.

The seller, who according to the listing was based in Germany, provided only minimal information about the origin and simply described the images as ‘photos from Greece from the Second World War’. The lack of detailed documentation is revealing in itself: these images were probably kept without any conscious historical intention, but simply stored away as family artefacts from a dark period.

The photos were offered with an estimated price of 500 to 800 euros – a shockingly modest sum for documents that today represent irreplaceable historical evidence.

What the photos show: A brutal documentation

According to reports by historians who have examined the images, the Kaisariani photos document:

1. The execution site itself – the barren landscape where 200 political prisoners were shot by firing squads.

2. German military personnel – clearly identifiable soldiers and officers who supervised the mass executions.

3. The victims in their final moments – haunting images of Greek communists sentenced to death, some of whom can now be identified by name thanks to cross-references with archival records.

What preceded the execution

The three occupying powers

Greece was divided between three occupying powers:

- Germany – controlled most of mainland Greece and the Aegean islands

- Italy – controlled the Ionian islands and parts of the mainland

- Bulgaria – controlled parts of Thrace and Macedonia

The German occupation zone, controlled by General Alexander Löhr’s Army Group E, included Athens, the Peloponnese and most of central Greece. This is where Kaisariani was to take place.

Collaboration and the Greek State

The Nazi occupation was not carried out solely through direct German administration. Instead, the Germans established a Greek puppet government under collaborative leadership. This government – initially under Ioannis Tsolakoglou and later under others – maintained the appearance of Greek statehood while simultaneously serving the interests of the Nazis.

The collaboration between the Nazi occupiers and the Greek puppet authorities is crucial to understanding Kaisariani. The executions were not a purely German operation, but were carried out with the participation of Greek authorities, the Greek police and Greek administrative structures. This collaboration would later lead to bitter internal conflicts and historical recriminations.

The resistance movement and the ELAS

A powerful resistance movement arose against the Nazi occupation. The dominant force was the ELAS (Elliniko Apeleftherotiko Socio, Greek People’s Liberation Army), the military wing of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE). By 1944, the ELAS controlled significant areas in the Greek mountains and posed a real military threat to the occupying forces.

There were other resistance groups, including nationalist and royalist organisations, but ELAS was by far the largest and most militarily effective. This fact shaped the nature of the Nazis’ reprisals: they considered ELAS and communism to be the greatest threat.

The immediate trigger: the attack on Molai in April 1944

The direct trigger for the executions in Kaisariani was an attack by resistance fighters on German troops near the town of Molai in the southern Peloponnese at the end of April 1944.

General Franz Krech and the 41st Fortress Division

General Franz Krech commanded the 41st German Fortress Division (41st Infantry Division), which was stationed in Greece as part of the occupying forces. Krech’s task was to maintain German control over the Peloponnese and combat the resistance activities of the ELAS.

The Molai incident

At the end of April 1944, ELAS fighters attacked German military positions near Molai. The attack claimed the lives of the general and four of his companions – estimates vary, but around 20 to 30 German soldiers were killed or wounded. For a military commander in occupied territory, this presented both a tactical challenge and a political problem: it showed that resistance forces could strike at occupation troops at will.

The doctrine of retaliation

The occupation forces operated according to a doctrine of collective punishment and mass retaliation. This doctrine had been formalised at the highest levels of the Wehrmacht and SS leadership. The principle was simple: for every German soldier killed by resistance fighters, a large number of civilians or political prisoners would be executed.

This was not ad hoc brutality, but systematic, rationalised and deeply embedded in Nazi occupation policy throughout Europe.

In Greece, as in Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union and occupied Western Europe, reprisal executions were a common tool of the occupation administration.

The 1:10 ratio and the Nazis’ reprisal calculations

The Nazis often applied a ratio of 1:10 or even 1:20 – for every German killed, 10 or 20 people were executed. In the case of Kaisariani, the execution of 200 prisoners suggests that the commanders had calculated this as an appropriate reprisal for the victims of Molai.

Major General Karl von Le Suire, the commander responsible for the Peloponnese, gave the order to carry out mass executions in retaliation for the attack on Molai. But the general did not act in isolation; his orders were in line with general German occupation policy and were probably approved by higher levels of command.

Selecting the victims: How 200 names were chosen

Once the decision to carry out mass executions had been made, the question arose: Who should be killed? The answer reveals the political dimensions of the Nazis’ occupation policy.

Political prisoners as targets

The occupying forces did not carry out random executions of civilians. Instead, they targeted political prisoners – men and women who had been imprisoned for resisting Nazi rule or supporting resistance movements.

There were several detention centres for political prisoners in Greece:

- Chaidari concentration camp – the most important facility near Athens

- Akronafplia fortress – in Nafplio

- Various local prisons – throughout Greece

- Internment camps – for people suspected of sympathising with the resistance

The decision to execute political prisoners served several purposes:

- Terrorism – to demonstrate to the resistance that capture meant death

- Elimination of perceived threats – removing committed opponents of Nazi rule

- Administrative convenience – the prisoners were already detained, identified and “processed” by the system

- Political message – specifically targeting communists and sympathisers of the resistance

The role of the Greek puppet government

Crucially, the Greek authorities were involved in the selection process. The Greek puppet government and the Greek police worked together to determine which prisoners should be executed. This collaboration later became a major point of contention in post-war Greek politics and court proceedings.

The Greek police and officials had detailed knowledge of the political affiliations and activities of the imprisoned individuals. They used this knowledge to help the Nazi occupiers identify those who were considered particularly dangerous or ideologically committed.

The focus on communists

Among the 200 selected for execution, most were communists or communist sympathisers. This reflected several realities:

- The ELAS was the dominant resistance force, controlled by communists.

- The occupiers viewed communism as an existential threat.

- The collaborating Greek authorities also saw communists as the greatest political threat.

- Communist prisoners represented the most organised and ideologically committed opposition to Nazi rule.

The execution was therefore directed not only against the resistance, but specifically against communism. This fact shaped the memory of this event and its politicisation in post-war Greek history.

The political dimensions: Occupation, collaboration and resistance

The resistance landscape

The Greek resistance was not monolithic. There were several movements:

- ELAS/KKE – communist-led, strongest militarily, controlled significant areas

- EDES (Greek Democratic National League) – nationalist/republican, allied with the Western powers

- Royalist resistance – supported King George II, who was living in exile

- Various other organisations – from across the political spectrum

By 1944, the main conflict was no longer just between the occupying forces and the resistance, but increasingly between ELAS and anti-communist resistance groups. This internal dimension would shape the post-war period.

The collaboration apparatus

The Greek puppet government, as well as the Greek police and security forces, actively collaborated with the Germans. Some of the motives for this were:

- Ideological agreement – some Greek fascists and conservatives considered communism to be the greatest threat.

- Self-preservation – collaborators wanted to maintain their power and avoid becoming victims themselves.

- Nationalism – some collaborators even believed that they were defending Greek interests against the occupation.

- Coercion – many Greeks were forced to participate in the occupation structures.

This collaboration apparatus became a highly controversial issue in post-war Greece and is still the subject of historical debate and political controversy today.

The role of the security battalions

Particularly noteworthy are the Security Battalions (Tagmata Asphaleias) – Greek paramilitary units recruited and armed by the Germans to fight against the ELAS. These units, composed of Greek volunteers or conscripts, became notorious for their brutality towards the communist resistance.

The existence and role of the Security Battalions led to a situation in which Greeks killed other Greeks in the name of fighting the occupation. This internal dimension made the occupation experience and the post-war period even more complex.

Current response from the Greek government and international diplomacy

The Greek government responded immediately to the eBay auction, with cultural and diplomatic representatives taking the following measures:

- Authentication: Experts from the ministry are travelling to Ghent in Belgium to verify the authenticity and legal origin of the photographs.

- Legal status: The Central Council for Modern Monuments will classify the collection as a ‘national monument’ in order to strengthen the legal claim for its return.

- The future: Following the acquisition, the photographs will be housed in the Greek Parliament, as agreed between the Ministry of Culture and the Speaker of Parliament, Nikitas Kaklamanis.

The response reflects Greece’s comprehensive commitment to restoring and honouring the memory of the victims of the Nazi occupation – a period in which some 300,000 Greeks lost their lives through fighting, executions, famine and concentration camps.

The man behind the photo

In one of the newly discovered photos from the archives of the Central Committee of the KKE, Kalafatakis can be seen wearing a white shirt next to Papadopoulos. For the first time in over 80 years, a face has been put to a name and a name to a story.

Who was Thrasybulos Kalafatakis?

Kalafatakis was born in Platania, Chania, in 1914 and came from a large, wealthy family involved in agriculture and dairy farming. From all accounts, he was an intellectually gifted young man with a passion for learning and a keen political awareness.

Early activity and political engagement

Even during his school years, Kalafatakis distinguished himself through his scientific engagement and political convictions. He joined the Communist Party of Greece and became intensely involved in party work, collaborating closely with KKE cadres throughout Crete. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who kept their political convictions secret, Kalafatakis openly professed his support for the communist cause – a dangerous stance in interwar Greece.

Resistance during the dictatorship

When the Metaxas dictatorship came to power in Greece in 1936, Kalafatakis did not retreat into silence. Instead, he intensified his underground work, organising young people and participating in activities against the dictatorship. This resistance came at a high price.

Arrested in 1939, Kalafatakis was sentenced to five years in prison. He was imprisoned successively in the prisons of Chania, the Averoff Prison in Athens, and the notorious Akronafplia Fortress. Over the years, he was transferred to internment camps, including the Chaidari concentration camp, where political prisoners were subjected to brutal conditions and an uncertain fate.

Marriage and family

Despite the turmoil of his political life, Kalafatakis married Aikaterini Hali, with whom he had two daughters: Maria and Ifigenia. Due to the circumstances of his arrest and imprisonment, his family endured years of separation and uncertainty, not knowing if he would ever return home.

The last day

On 1 May 1944 – International Workers’ Day – Kalafatakis was among the 200 prisoners executed at the Kaisariani firing range. He was 30 years old. The Nazi occupation of Greece continued, and the execution was a brutal reminder of the price of resistance.

In honour of his memory

In recognition of Kalafatakis’ unwavering commitment to his political beliefs and his sacrifice, the municipality of Chania named a district after him – the Agios Loukas area now bears his name to ensure that future generations remember the young man who put principles above safety.

A greater historical tragedy

Kalafatakis’ story is one of 200 similar tragedies that occurred on that one day in Kaisariani. Recent identification work by the KKE — based on the party’s archives, Central Committee records and witness testimonies preserved in documents such as ‘Kaisariani Shooting Range’ (November 2016) — represent an important act of historical remembrance.

The newly discovered photographs and biographical details offer researchers, historians and descendants the opportunity to reconstruct the lives of those who were wiped out by state violence. Each identified victim becomes a challenge to historical oblivion.

The other victim: Dimitris Papadopoulos

Among those identified alongside Kalafatakis is Dimitris Papadopoulos, a Pontic refugee who came to Greece in the 1920s. Papadopoulos was a construction worker and trade union organiser who rose to become general secretary of the construction workers’ union. Between 1928 and 1936, he played a decisive role in organising labour disputes, which led to repeated arrests, imprisonments and exiles.

In 1936, he was arrested and sent into exile; he was later transferred to Akronafplia. In 1941, the Greek authorities handed him over to the Nazi occupation forces, and he was taken to the Chaidari camp. Like Kalafatakis, he was executed on 1 May 1944.

The ultimate sacrifice: The heroic death of Napoleon Soukatzidis in Kaisariani

On 1 May 1944, a man from Asia Minor was faced with a decision that would shape his legacy forever. When offered the chance to escape execution, Napoleon Soukatzidis refused – instead, he chose to stand before the Nazi firing squad alongside 199 of his convicted comrades. His decision transformed a mass execution into an act of profound moral witness.

The execution of 200 political prisoners at the Kaisariani firing range on 1 May 1944 remains one of the most decisive and tragic events in modern Greek history. Among these 200 names, however, one story stands out in particular due to its extraordinary moral dimension: that of Napoleon Soukatzidis, a communist activist and intellectual whose final decision illustrated the true meaning of sacrifice.

A life of principles: from Asia Minor to Crete

Napoleon Soukatzidis was born in 1909 in Prussa (now Bursa in Turkey) and came from a region whose Greek inhabitants would soon face the catastrophic consequences of the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922. Like hundreds of thousands of others, his family fled from the Turkish nationalists and sought refuge in Greece, where they eventually settled in Arcalochori on Crete.

Despite the trauma of displacement, the young Napoleon aspired to education and intellectual development. He graduated from the Heraklion Commercial School and worked as an accountant, a profession that reflected both his academic abilities and his practical skills. But numbers and account books were never his true passion; politics and social justice consumed his intellectual energy.

The polyglot communist activist

Soukatzidis was a man of considerable intellectual gifts. He was multilingual and possessed the sensibility of a writer, penning essays and articles on political and social issues. These talents made him a natural organiser and spokesperson within communist circles.

He became an active member of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and was heavily involved in trade union work. In Heraklion, he rose to become president of the trade union for commercial employees and used his position to campaign for workers’ rights and social reforms. His work was not limited to economic demands, but reflected a broader revolutionary consciousness shaped by Marxist ideology and an unwavering commitment to communist principles.

Under the Metaxas dictatorship

When Metaxas’ dictatorship descended upon Greece in 1936, communist activists such as Soukatzidis were immediately persecuted. He was arrested and exiled to Ai Stratis (Saint Stratis), a remote island prison used to isolate political prisoners from the mainland.

In 1937, he was transferred to the Akronafplia Fortress in Nafplio, where conditions were slightly less harsh but the isolation was just as devastating. The fortress held some of Greece’s most committed revolutionaries – men and women whose refusal to renounce their beliefs made them permanent inmates of the state prisons.

Into the abyss: Soukatzidis under Nazi occupation

When Nazi Germany invaded Greece in April 1941, the fate of political prisoners hung in the balance. The occupying authorities had little use for Greek communists – they regarded them as enemies of the Third Reich and a potential threat to order. In a sinister agreement, the Greek collaborationist government under Nazi control handed over communist prisoners to the Gestapo.

In April 1941, Soukatzidis was transferred from Akronafplia to Nazi custody. What followed was a descent through a series of prisons and concentration camps:

* Trikala Prison – a detention centre for political and military prisoners

* Italian concentration camp Larissa – where conditions deteriorated dramatically

* Concentration camp Chaidari – the notorious facility outside Athens where thousands died from disease, malnutrition and brutal treatment

A valuable prisoner: The burden of the interpreter

Amidst the brutality of camp life, Soukatzidis occupied a special position. Because he spoke fluent German, the German camp authorities recognised his usefulness as an interpreter. This rare skill earned him certain privileges – better food, lighter work and, above all, a degree of relative safety.

In the calculus of survival in the concentration camp, being useful to the guards meant the difference between life and death. Soukatzidis’ fluency in German was his insurance policy – or so it seemed.

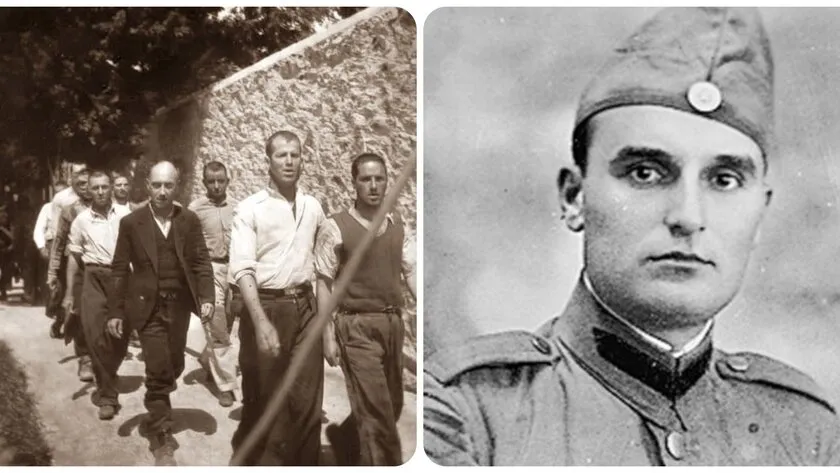

1 May 1944: The decision that changed everything

At the end of April 1944, the Nazi occupation forces in Greece faced a significant military challenge. General Franz Krech, commander of the 41st German Fortress Division, had been murdered near the town of Molai by fighters from the ELAS (the Greek Communist People’s Liberation Army) – the communist-led resistance group – along with four of his companions.

In retaliation for this attack, the occupation command ordered a mass execution: 200 political prisoners were to be shot. The victims were to be selected from among the prisoners in Chaidari and other detention centres. It was a cruel and brutal decision – a collective punishment of the helpless.

The camp administration compiled lists of names. When they came to the name Napoleon Soukatzidis, something extraordinary happened.

The moment of truth

According to the statement made by Soukatzidis’ cousin Photini Soukatzidis, who told the story to the German newspaper Bild in 2018, the camp commander paused when he read Soukatzidis’ name. The commander looked up and spoke words that represented a lifeline:

‘There has been a mistake. You should not be on this list. We will put someone else in your place. You will not go.’

The reason was clear: the Germans needed Soukatzidis as an interpreter. Without him, communication between guards and prisoners would have been more difficult. His language skills made him indispensable – a rare quality in the camps.

It was a moment that would determine the rest of Soukatzidis’ life – or rather, his last hours.

Soukatzidis asked a simple question: ‘Will you put someone else in my place?’

The commander confirmed: ‘Yes, because we have orders for 200 people.’

What Soukatzidis said next reveals the moral foundation of his character. According to Photini’s account, he replied:

‘A mother will cry for me, and a mother will cry for someone else. I will not return.’

This was not the statement of a man acting for the sake of glory or martyrdom. It was the statement of a person who had grasped a fundamental human truth: that his life and that of another were not his alone to dispose of. His responsibility to 199 other people and their families weighed more heavily than his own survival. Accepting liberation would have meant condemning an innocent person to death in his place.

Soukatzidis decided to rejoin the ranks of the condemned.

The swan song

Photinis’ statement continues with a detail that has become iconic in Greece’s collective memory. As the condemned men were led to the firing squad in Kaisariani, Soukatzidis sang. According to reports, he sang a revolutionary song – perhaps the ‘Internationale’ or another anthem of the labour movement – as he approached the executioners’ rifles.

On 1 May 1944 – International Workers’ Day – Napoleon Soukatzidis was executed by a Nazi firing squad along with 199 others. He was 35 years old.

The weight of sacrifice: why Soukatzidis’ death mattered

The photograph that remains from the day of the execution tells part of the story. In the newly discovered images of the mass execution at Kaisariani, we see the faces of men facing death with a dignity that the brutality of the Nazis could not erase. Among those faces was that of Soukatzidis.

But it is the decision that gives his death special significance. In a concentration camp system designed to reduce people to numbers and objects, Soukatzidis affirmed his humanity and his moral capacity to act. He could have lived. He chose not to – not out of despair or a death wish, but out of solidarity with those who had no choice.

This makes his execution a ‘sacrifice’ and not just a tragedy. A tragedy is something that happens to us; a sacrifice is something we choose to do. Soukatzidis transformed his inevitable death into a meaningful act of testimony.

Historical memory and cinematic resurrection

The story of Napoleon Soukatzidis might have remained unknown, known only to his family and Communist Party historians, had it not been for the efforts of filmmaker Pantelis Voulgaris. In 2017, Voulgaris made the film Teleftaio Simeoma (The Last Note), which focuses on Soukatzidis’ personal story and his final act.

The film is considered one of the most emotionally powerful works of modern Greek cinema, transforming a tragedy from the archives into a lived human experience. Through Voulgaris’ direction, a new generation of Greeks learned the story of a man who put solidarity above his own survival.