The history of Crete in the 20th century after the unification with Greece (Part VII).

The history of Crete in the 20th century

The history of Crete in the 20th century was marked by significant political, social, and economic changes.

Overview

Early 20th Century:

– 1898-1913: Crete was an autonomous state under Ottoman suzerainty but effectively under Greek administration.

– 1913: Crete was officially united with Greece following the Balkan Wars.

World War I and Interwar Period:

– 1917: Greece entered WWI, and Crete served as a base for Allied operations.

– 1923: The Treaty of Lausanne led to a population exchange between Greece and Turkey, affecting some Cretan Muslims.

World War II:

– 1941: German forces invaded Crete in the Battle of Crete, a significant airborne operation.

– 1941-1945: Crete was under Axis occupation, with strong resistance movements developing.

Post-World War II:

– Late 1940s: Crete experienced economic hardship and participated in the Greek Civil War.

– 1950s-1960s: Gradual economic recovery, with tourism beginning to emerge as a significant industry.

Military Junta Period:

– 1967-1974: Greece was under military dictatorship, affecting Crete’s political landscape.

Late 20th Century:

– 1974: Return to democracy in Greece.

– 1981: Greece joined the European Economic Community (later EU), bringing new opportunities and challenges to Crete.

– 1980s-1990s: Rapid development of tourism infrastructure and services on the island.

Economic and Social Developments:

– Throughout the century: Gradual shift from an agricultural economy to one based increasingly on services and tourism.

– Improvements in infrastructure, including roads, ports, and airports.

– Urbanization, with growth of cities like Heraklion and Chania.

Cultural Preservation:

– Efforts to preserve Cretan traditions, music, and dialect intensified in the latter part of the century.

Environmental Concerns:

– Late 20th century saw growing awareness of environmental issues related to tourism and development.

The 20th century transformed Crete from a relatively isolated, agricultural society to a modern, tourism-oriented economy within the framework of the Greek state and the European Union.

Crete in the Second World War

In the fall of 1940, Italian troops invaded northern Greece, only to be repulsed by the Greek army across the Albanian border. Mussolini’s humiliation, however, only served to draw the Germans into the fight. Although British troops were sent to Greece, the mainland was quickly overrun in the Balkan campaign.

From the beginning, the Allied campaign was marked by mistrust, confusion, and lack of communication between the Greek and British high commands. On the Greek side, dictator Metaxas had died in January and his successor as prime minister committed suicide in defeat, leaving a native of Crete – Emanuel Tsouderos – to organize the departure of the king and government to his home island.

They were quickly followed by thousands of evacuees, including most of the Allied Expeditionary Force. This force was largely made up of Australian and New Zealand soldiers. Most of the native Cretan troops, who formed a division of the Greek army, were lost in the defense of the mainland.

Battle of Crete

According to the Allied plan, Crete was supposed to be an impregnable fortress by now. In practice, however, virtually nothing had been done to improve the island’s defenses. Thus, there were hardly any operational aircraft or other heavy equipment, and the arriving troops found little plan for their deployment.

On May 20, 1941, the invasion of the island began as German troops landed by gliders and parachutes. At first, it was a grisly slaughter, with the attackers easily shot down on their slow approach to land. Few of the first wave of parachutists reached the ground alive, and many of the gliders crashed, crushing the mass of German airborne troops before they even reached the ground.

In the far west, however, they managed to capture the airfield at Maleme. Whether due to incompetence – as much of the literature on the Battle of Crete suggests – or a breakdown in communications, no attempt was made to retake the airfield until the Germans had enough time to defend it. With this bridgehead secure, they began flying in reinforcements and equipment.

Shortly before the battle, the German code keys had been broken, so the Allied commander on Crete, General Freyberg, knew in detail where and how the attacks would be made. However, since he was not allowed to pass the secret intelligence to his subordinate officers in order to protect the source, a fatal misunderstanding in the chain of command about the enemy’s intentions contained in the information led to the Allied forces at Maleme being reduced.

From that moment on, the battle that was supposed to have been won was lost, and the Allied troops, already under constant air attack, came under intense pressure on the ground as well, which they could not withstand.

The losses of the Battle of Crete were enormous on both sides, and the cemeteries are reminiscent of the burial grounds of the victims of the First World War in northeastern France. The best German airborne division was practically wiped out, after which the downed Hitler erected a monument to it, which still stands outside Chania. No one ever attempted a similar attack again.

But once they had established a secure bridgehead, the Germans advanced rapidly, and a week after the initial landing, the Allied forces were in retreat over the mountains toward Hora Sfakion, from where most were evacuated by ship to Egypt.

On May 30, 1941, the battle was over, and several thousand Allied soldiers and all the Cretans who had fought alongside them were forced to surrender or flee to the mountains.

The Resistance

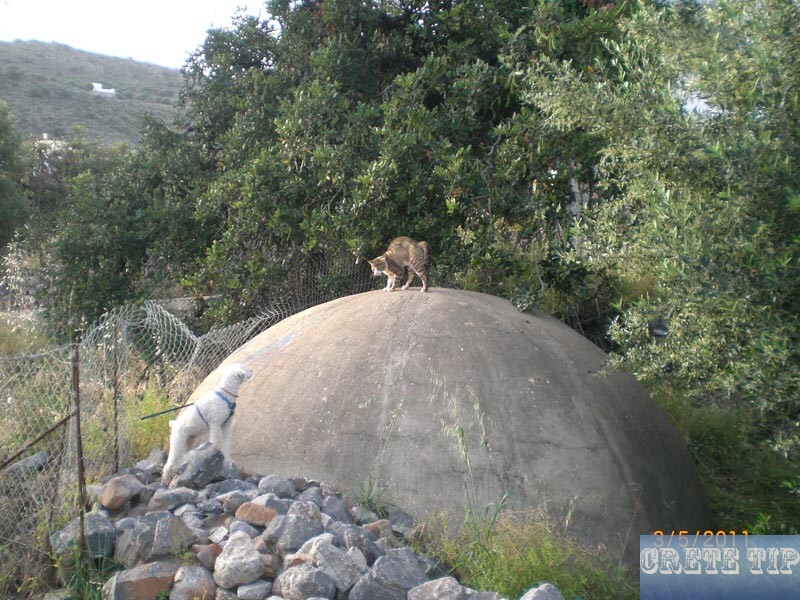

One of the first tasks of the resistance was to get the still scattered and remaining Allied soldiers off the island. In this they had remarkable success: they gathered the scattered into groups and organized their pickup by ship or submarine from the remote beaches on the south coast. Many were hidden and fed by monks while they waited to escape, most notably the monastery at Preveli.

In this respect and in many others, the German occupation resembled the previous occupations of Crete – there was constant resistance and brutal reprisals.

The north coast and the lowlands were controlled easily and safely, as in the past, but the mountains and especially Sfaki remained the stomping ground of rebels and resistance groups throughout the war.

With the boats that took the survivors of the battle away from Crete came British intelligence officers, whose job was to organize and arm the resistance. Throughout the war, about a dozen of them stayed on the island, living in mountain huts or caves, trying to organize parachute drops of weapons and report on troop movements on and around the island.

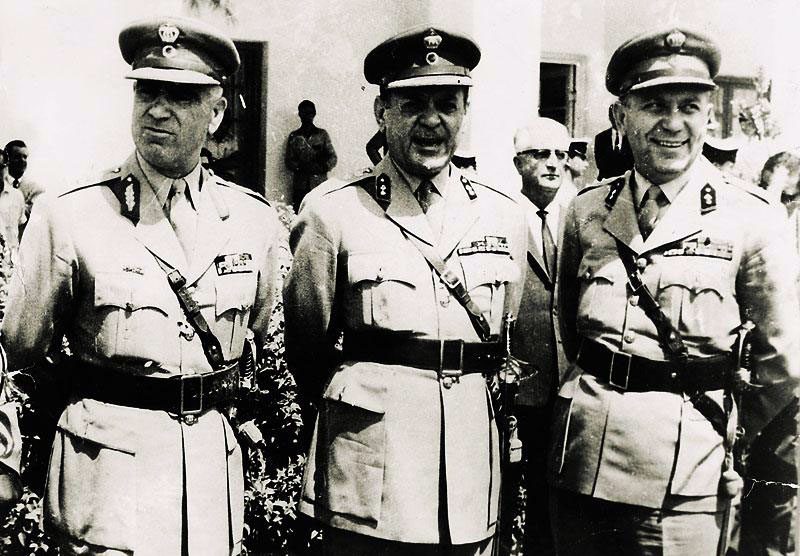

How effective the sporadic efforts of the resistance on Crete were during the war is difficult to judge, and it is questionable whether actions such as the kidnapping of General Kreipe brought the end of the war closer, while resulting in numerous casualties, especially among the civilian population.

The kidnapping of General Kreipe:

The immediate result of this propaganda coup, however, was a terrible campaign of revenge against the Cretan population, in which a number of villages around the Amari Valley were destroyed and all the men who could be found were slaughtered.

Harsh reprisals against the Cretan civilian population were the usual response of the German army to any success of the resistance.

In late 1944, German troops retreated to a heavily fortified defensive line around Chania, where they held out for seven months before surrendering at the end of the war.

This created a power vacuum on the island, which several resistance groups hastily tried to fill. The Allied intelligence services could claim beyond doubt that one of the achievements of their agents on Crete was that the civil war that shook the rest of Greece was all but avoided here.

On the mainland, the organization of the resistance was largely the work of the Greek Communists, who emerged at the end of the war as the best organized and armed group. In Crete, the groups that sympathized with the Western Allies were the best armed and organized. Especially in the last phase of the war, the communist-dominated organizations were deliberately left with little equipment. There were few violent incidents on the island, and these were quickly put down.

Post-war period

Since the civil war was largely avoided on Crete, it was also possible to start reconstruction there earlier than in the rest of Greece. As a result, after 1945 the island developed into one of the most prosperous and productive regions of the country.

Politically, Crete was deeply suspicious of outside control, even from Athens, in the postwar period. This circumstance persists to this day. Particularly at the local level, loyalties are divided along clan and patronage lines rather than along party lines, and leaders are judged by how well they take care of their areas and their followers.

Cretan local politicians at the local level continue to take an almost unanimous pleasure in defying central power. There is also no separate island government, only a regional administration run by officials from Athens.

In one famous incident, the mayor of Heraklion organized a sit-in at the Archeological Museum to prevent artworks from being taken abroad for exhibition: Fifty thousand people came to support him, and although President Karamanlis ordered his arrest, the central government eventually had to relent.

There are also fierce rivalries within Crete, especially between Chania, which was briefly named capital at the beginning of the century, and Heraklion, the traditional and current capital and nowadays also the richer and more politically important city.

This fragmentation leads to all sorts of anomalies and compromises: symptomatic was the rather impractical decision to divide the University of Crete among three locations, namely Heraklion, Rethymno (which has always considered itself the most cultured city in Crete) and the autonomous polytechnic of Chania.

Within Greek politics, the island appears more united, representing the liberal tradition of Venizelos. The 1967 anti-leftist coup in Athens that brought the junta of colonels to power was passionately opposed in Crete, making the island one of the few regions in Greece to openly resist the regime.

Seven years of repression followed, during which all political activity was banned, the press was heavily censored, and communists were arrested, imprisoned, and tortured.

In a referendum following the overthrow of the colonels in 1974, Crete voted overwhelmingly against the restoration of the monarchy, since the king had been involved in the coup, and instead voted for a republican system.

In subsequent presidential elections, support for the far-right Karamanlis – and the subsequent winner – was less than half as high in Crete as in the rest of Greece.

This has been a consistent pattern: the left-wing PASOK has always received twice as many votes in Crete as the more right-wing ND.